Police State

You’ve heard things. Everybody has. In this or that neighborhood, someone undocumented being seized. The stories coming out, it feels almost like Germany. Police cars roll past you on the street and your heart starts thudding in your chest.

Friday, town and errands behind you, you see ahead, at a crossing, vehicles plastered everywhere, and uniforms.

Slowing to a crawl, a cop in your path, you tap your phone and hold it up above the steering wheel. You stop the whole way, get your window rolled down. Now the lime vest and the dangly keys and the cop’s clip-on squawk box loom up close. Now you’re aiming at her face.

I need to see your driver’s license, she says.

Somewhere around here is when you put down your phone.

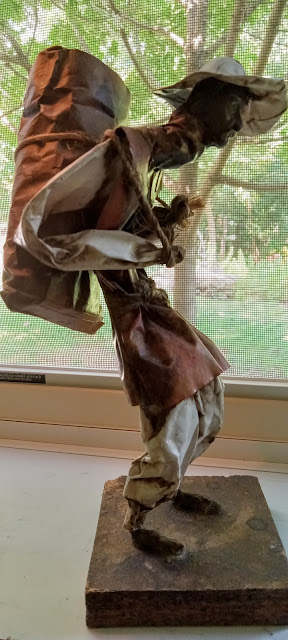

It’s in the trunk, you say. You don’t explain, but you’ve got your junk store purchases back there in a box. When you left the store, not wanting the flowerpot and the glass lamp to bang against each other on the way home and break, you wedged your soft money pouch down in between.

Briefly she considers. Then she says you can get out. Here’s where you begin recording again.

Your door pushing open. Your route around to the trunk. The lid popping. The cop’s feet and legs and vest, and her fingernail polish—her hand extended, waiting. Your own hand pawing for the license. The cop examining it.

Okay, she says, go ahead and get me your registration, too.

So why are you checking my license? you say.

Well, we’re checking all of them for our sobriety checkpoint. Uh, but you rode up with your cellphone in your hand so I’m gonna issue a citation for you for that. So if you could go ahead and get me your registration.

No, you bluster, I think it’s—I think I’m perfectly legal in—in—

Okay, well, holding a cellphone while you’re driving is not legal, so go ahead and get me your regis—

Oh, I was—I was—

You were not stopped.

I was stopping, ma’am. I was stopping.

Your vehicle was—

Nobody, you say loudly, is drunk.

Okay, I’m not saying—

You bawl, At two o’clock on Satur—on Friday afternoon—

Okay, please get me your registration.

Your face, indignant. Her feet, your feet, the muddy ditch. Then your filming cuts off.

You wait behind the wheel while she does the paperwork for your summons. She checks the box where it says you can waive your right to appear in court. You can mail your payment, instead. Your signature indicates only that you’ve been notified. She lists the charge, the codes. When she’s done she asks if you have any questions.

You ask, Have you ever before done drunk-driving checks on a Friday afternoon?

She looks at you. Any questions, she says, about this paper?

You sit there groping for words.

You know why I was filming, you say. She’s watching you, impassive. But maybe not closed off—not her eyes. You can’t tell what’s behind. There’s maybe a spark. These kidnappings, you say. We all have families. Something’s awfully wrong in the world.

Quiet, she tears off your yellow copy, hands it over. She walks away. Alone in your car, you pick up your phone again and pan the scene. Gray clouds, gray macadam. Motor noises. Indolently moving cars, and some kind of commercial truck for hauling live cattle, headed south. The uniformed man in the middle of the intersection, his elbows out, legs apart, the way they teach cops to stand, no doubt. The extra vehicles parked up on the hill, where they also have a dog.

And then when you get home and check your phone, you can’t find that illegal, fumbling, first stretch of footage—the cop ahead on the road, and then her requesting your license.

Your camera wasn’t on. Dumb dumb dumb.

Dumb dumb dumb dumb dumb.

You do have the trunk lid opening, the cop’s bossing, your protestations. You do have, under the dull sky, the cattle truck turning left, toward Harrisonburg.

The thudding’s slowing down.

Comments

Post a Comment