She’s gone.

Her last Sunday, we missed. A few days later I thought I might still find her. I saw the doors were open—not the doors closer to her office—and a van was parked on the walkway, with some kind of industrial hose snaking from it up into the church, and when I got to the top of the steps, a man was machine-scrubbing the carpet. He let me pass—I took off my flip-flops—and I padded through the big wet empty fellowship hall, ducked under the yellow tape in a doorway, and barged into the office. But she wasn’t there anymore.

I don’t even have a photo. She came only once to our house, for the Chuck & Franny reading, so here’s the dark hair and glasses—that’s all. But I still have the note she sent later. It astounds me, now—the pleasure she took from the gathering, and from the play, and the length to which she went to let me know. She even referenced particular scenes. “The green bean tips,” she wrote, “the cat poo in the sandbox sand and sniffing the mortar, the stolen Sheetz creamers. I loved it all.” By then, though enough of my spunk had drained out of me. I couldn’t see more fiddling with the manuscript, fiddling, fiddling, and then getting the story to an audience.

The only other time I saw her away from church, she was just settling in for her lone year here. Somebody was hosting a potluck, a get-acquainted time, and my husband and I ended up across the dining table from her and Robert. The different conversations going on in the room, people shrieking and laughing, and Robert’s British accent, thick as mud, every time he opened his mouth—we could only get snatches. Gwen’s background, though—Pennsylvania—meant the two of us knew much the same things. At a church meal later in the year, the crowd thinning, we hunched together in our folding chairs bemoaning the state of the world and the depths to which family members—hers and mine—had sunk, trusting filthy lying politicians. Her brown eyes snapped. Mine—blue—rolled.

Her last sermon I was at church for, oh my. Afterwards, I went up front. People were up there talking with the pianist—she’d read a poem, during the service, but broken down crying partway through, and I’d not been able to catch some lines. Gwen—she knew I was waiting for her—sat down on a chair near me and I asked would she let me have her sermon. Later she emailed it.

We don’t, in some objective, isolated vacuum, decide what we believe, she says here. No, we’re born into families and communities and cultures, and from within those circles of belonging we work out what it is we believe. The beliefs grow out of our experiences. We can’t actually decide what we believe. We notice what we believe. Then we choose what to do about it.

Not everyone here at church believes the same, she says. We don’t pretend to. We don’t think we have to. That goes for our leaders, too. We have no pope, no bishops. We don’t have to pretend to agree with the leaders’ beliefs. We don’t have to believe anything she’s saying, or with what Jason preaches.

And even better, she says, none of us has to believe what we used to believe. Jason doesn’t believe what he believed 20 years ago when he came here. She doesn’t believe everything she believed when she came last May. Beliefs should evolve. If our beliefs don’t change over time based on our experiences, we’re not listening to our lives.

It pretty much knocked me over, listening in my seat.

Gwen never preach preached. She read out her lines in a dry, flat, slightly scratchy voice. That in itself would’ve almost been enough. I have to confess, though, that her first Sunday, what first impressed me was her shoes. Just comfy. Not stalky heels. In the plainest of ways, purely classy. I don’t know about those selfsame shoes months later, the last Sunday I saw her, but I’m thinking it had to be those. She had on the familiar, flowy black pants and top, anyhow. I have to wonder, now, if that’s what she always wore. I never kept track. And now, oh, I miss her.

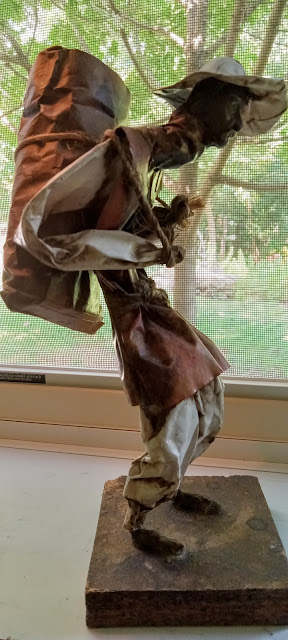

(Photo credit: Jennifer)

Comments

Post a Comment