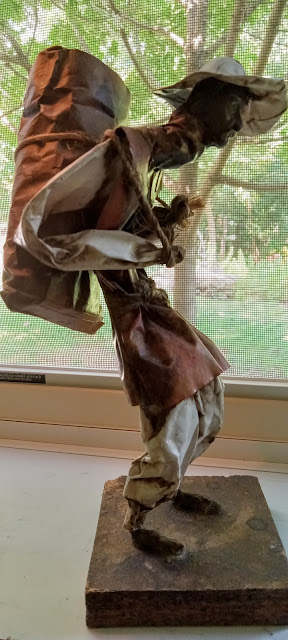

Framed-Art Tour, Exhibit 14

It’s just there, always at his back, taking brainless note of his moving elbows, his bent head, his tap-tapping laptop keys, his words and numbers jiggling onto and off of the screen. Or, in bits and spurts, his Nunatsiaq News scrolling, or the Guardian’s or New York Times’s coverage of the shredding of a nation—the blinkering, shattering reports.

(Or in the evenings, very late, some howling rock band some 40, 50, 60 years ago.)

That’s if he’s there. Stuck on the study wall like it is, opposite his desk drawers and the spindled back of his desk chair, it can’t keep track when he’s gone. During the day my husband might, instead, be out in the actual off-the-art-paper forest. He’s getting away, calming his nerves. Maybe doing woods patrol, as he calls it.

He’s combed the whole place for nonnatives. He’s decimated the beebee trees and the trees of heaven. He’s taken out the Japanese honeysuckle, the beefsteak plants, the garlic mustard, the multiflora roses. Yet the nasty foreign seedlings and shoots keep showing themselves. They must, he thinks, be pulled or poisoned, yay, to extinction.

(Not yay yay, like when you’re cheering your team on. Yay as in yay vs. nay. Poisoning is onerous, shame inducing. Also ironic, because isn’t the fabulous thing about nature its obstinacy? Its pluck, its will to rise and rise and rise again?)

(He hates this part of the job and does it rarely, now, and gingerly.)

And then, some days, he’s a worse invader than the aliens. Suited up like somebody on a goon squad, he does his other important culling, gaining lumber and firewood. Sunlight must come through. The amiable elders must make way. One after another, he rips his chainsaw through the tree’s age circles, shrilly but not with animosity, until there’s a mighty crack, then the sound of grating leaves and branches, of the giant flopping to earth.

Sometimes he only brings his friends to their knees. He whacks only partway through a young tree’s core, so that after the felling, still hooked to the stump, the trunk makes a sort of bridge, angled and low to the ground. Squirrels and children can scamper along the length. Beneath the dying, crisping branches, the bugs and bees and luckier rabbits can hide and snack and maybe construct new civilizations.

Everything was a jungle, when we came. We’d bought a jungle. You had to fight your way through.

For the house and the drain field, we hired a bulldozer. Lots quickly toppled. Not the thicket, though, near the pit for the house foundation. There, my husband whacked off enough growth to allow for a bathing hut, and our tent, and a fire ring where we could make pancakes. To this day the patch of wood stands, a few bumpy, grassy yards from the porch, still tamed, looking something like the copse in the picture.

Dale’s Woods, my husband calls it now, because his friend Dale likes for land to be forested skimpily. It’s the spot for the trampoline, the sandpile, its overstory a relief in torrid weather. On a brutal morning this summer, Rick and Orv and Timothy—my husband’s buddies group—came anyway and he put out lawn chairs and took out the coffeepot and they had their fine time. But if he’d tried marching them downhill and into the steamy wild, the part that’s still enough of a morass for feral creatures’ habitation, the guys would’ve rebelled. They’d not come to massacre or prune or even smell the flowers.

Does a man who goes daily to the woods need a picture of trees?

I’m always eyeing the walls, wondering what might go where better. But he doesn’t want this piece of the world moved. He wants the trees there—right there. He likes their likeness, the artly homage.

Love this piece!!

ReplyDeleteWhat an incredibly skillful homage to the artly homage!

ReplyDelete