Asako Yuzuki, Butter, translated by Polly Barton, HarperCollins 2024

He had it coming through his earbuds, Zachary told me. He said Akiko was reading it. Obviously, I had to look into it.

I got just a few sentences in, waiting on a chair in Target for my vaccines, before the pharmacy person called me over. Not the best start. Then it took me weeks to get through—my library copy, here, is fat-lady thick. They’ll soon be demanding it back.

(If that upsets you—fat lady—I say check it out, yourself.)

Sometimes, reading, I had to labor over who was speaking—I needed a he said, or she said. And the little I knew about Japanese culture only flummoxed me. The mochi, my word. In my mind these were the delicate, dough-coated treats Akiko gets at Trader Joe’s in Pittsburgh, ball shaped, filled with ice cream.

In Butter, Rika’s mom has brought her some. They’re fresh. “Do you want to grill them?” asks Mom.

Rika washed her hands then arranged the smooth, pre-cut mochi dusted with rice flour inside the toaster. Wait. What?

Watching the corners of the mochi slowly filling out against the toaster’s crimson-lit insides, mother and daughter fell quiet. Huh? Huh?

The mochi gradually began to take on colour and swell out. When their skin seared with brown grill marks started to split open, revealing glimpses of their sparkling white insides, Rika took them out of the toaster.

How long it took me to come to my senses, I don’t know. The mochi in Butter are the traditional, gluey beaten-rice delicacies Akiko introduced us to. We made it last Christmas—she had us pounding the rice in a hollowed-out piece of tree trunk. She said people can choke to death, eating it.

Where was my head?

(Those whatever-they’re-called ice cream balls—I do love them.)

Sometimes I worried that the translator’s English—Polly’s—had failed her. Here are Rika and Shinoi at Shinoi’s house, very late. Having never made a cake, and no oven where she lives, Rika is using Shinoi’s equipment. She’s sieving the flour. He tells her to add in baking powder. Rika stopped moving. The flour falling softly through the metal mesh formed a tiny tornado the width of her fingertip. The remaining clumps rolled forlornly around in the sieve. Lonely clumps—I liked that. But Rika had quit sifting. They rolled? Beneath the sifter, the flour stormed?

And then, the kitchen warming up, Rika sheds her coat, takes it to the living room. When she re-entered the kitchen, [Shinoi] began issuing her with instructions. Whoa. My eyebrows went up.

But more often, it was my English failing me. Later in the story Rika, taking pains to please her friends with her cooking, manages sea urchin with beurre blanc sauce. She’d also splashed out and bought herself a new apron. No no, I wailed in my head, she’d splurged. But later I checked. “Splash out” was right there in the dictionary.

I had to work my way through elaborate conversations, lengthy ruminatings. But the story carried me along. I didn’t just puzzle. I also took pleasure, like Rika with her food. [The butter] flavour grew golden and staked its territory, with a kind of violence. A certain depth of flavour began to assert itself, and as the droplets plummeted to the centre of her body, its arc of influence expanded. Another instance: When she chewed [the grains of rice], the inside of her mouth loosened, and when she made to greedily absorb them and taste them, she could feel the insides of her body whirring round as if all its cogs were moving.

(This is not how I eat. Sometimes ecstatically, yes, but never with such attention to my own bones and gut.)

At the end there’s a wonderful wonderful turkey story.

I’m not getting into Butter’s issues, here. I’m shirking. I’d have to say this and this and this—try to disentangle the societal factors—and I’d make a mess of it. But at the heart is the problem of loneliness.

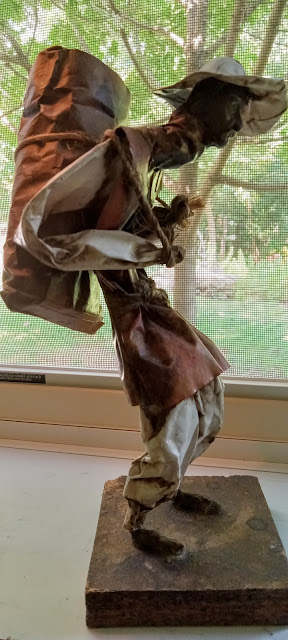

Murder, says the book jacket. (In English, anyhow. In Japanese—here’s Akiko’s photo—who knows?) That word gets your attention, doesn’t it? If you’re thinking I just read a whodunnit, though, think again.

That butter dish could almost be mine. Or maybe it’s not for butter. Maybe it’s one of those hotel room-service plate-and-dome things the waiter wheels in on a trolley. But if it’s meant to hold butter, I have one similar—metal, clangy. Not that this is of any significance.

I'm smiling a twinkly little smile, because, yes! I know that sometimes you're able to eat green beans ecstatically. And sometimes then you're even cooking such gustatory delights that all around your table are eating ecstatically, as well!

ReplyDeleteHa, they're coming up next—the beans.

Delete