When the Parents Fluttered Away

Brother Touslyhead takes the bigger bed upstairs, where I can read to him from the purple chair. Sister Ringlets and her math and psych textbooks, the one across the hall. Sister Braids gets my husband’s and mine downstairs, right around the corner from the living room. So where does that leave us?

It’s all right. I love it on the sofa. It’s where I take up camp whenever I’m fevered and hacking, or too riled by the manic dead-of-night thoughts to sleep. This time, both of us chased from our bed, we’re elaborately stocked with pillows, blankets, and all, and from my berth I can still hear his breathing inches away, his toasty warm stirring, down on the floor. He’s even put his clock like he likes it, approximate to his bedding, the numerals lasering a path to his eyes.

For four whole nights the arrangement works just fine. Grandparents are adaptable, right? They can handle things, right?

There’s extra laundry, of course. At the machine one morning, Touslyhead suddenly at my side, I hold out my hand to show him the limp insect I just pulled from the water. “A silverfish,” I say. “No, earwig.”

“It might be one of those bugs that gives live birth,” he says. “Tsetse flies do this. They have one or two babies and they come out really big. And cockroaches give milk.”

He explains. Instead of laying 100 eggs, the cockroaches have 8 to 18. They keep them in a brute sack that fills up with milk and the babies ingest it.” That’s what he says, ingest. “After 50 or 70 days they’re born. For tsetse flies, it’s like 10 days. They maybe have milk, too. The scientists get the cockroaches’ milk out using a cloth that absorbs. They stick it into the brute sac.”

“Brute sac?” I say. “Boot, you mean? Or broot?”

“No, brute.” He spells it out. B-r-u-t-e.

“You should listen to the Ologies podcast,” says Touslyhead. “The bonus part, about the milk. They find these cockroaches at popular tropical destinations.” That’s how he puts it, tropical destinations. “Some places in Asia, Hawaii, maybe Japan. They live at a lot of these places. It’s not really milk. It doesn’t have lactose.”

Then when I’m in the yard hooking his red T-shirt to the wash line, he comes dashing out of the house. “Also, the cockroaches’ milk is edible and nutritious. People have eaten it. But they water it down because it’s very precious. From each cockroach they get only an extremely small amount.”

“How small?” I ask, later.

“Well, imagine a cockroach. “Imagine the little sac. Imagine how much. It would take a lot to make just one little latte.”

Eventually I look up it up—brute sac. Oh, brood sac. Okay. But I opt not to verify the rest. I’ll take it for what it’s worth.

Obviously, too, there’s more going on in the kitchen. Food food food, not all of it my doing. Sunday morning, my baked-potato chunks browned to a crisp, the skillet pushed to the rear of the stove, I scoot back to the sofa. People can get whatever else they want.

Clanging of pans. Babbling. From my island of rumpled sheets I’m able to listen in.

“Four years more—only four—and I get the world’s respect,” says Sister Ringlets. She’s 17. “No money, but society will expect me to be be living on my own and holding a full-time—probably—job and be self sustaining.” It almost sounds like she’s exulting. Maybe not. “You’re a teen and then, boom, they spit you out. They expect you to go out and find a job. Are there any societies that don’t? Because I want to go there.”

Her sister and brother are chorusing along and interjecting, but she overrides. “Guys, I recommend community college. Because it’s nice. I have availability bias—that’s where you come to conclusions based on the knowledge you have, which could be false.” Huh? “I don’t care, though. If community college is this fun, then real college must be more fun.”

On and on.

Yakety-yak, yakety-yak.

Every conceivable topic. The state of the world, what-all else. It’s practically a colloquium.

I hear somebody say, “Things would be better if Mennonites were in charge.”

“No they wouldn’t,” says another. “Well, better, but not great. If Andrew Peyton would be president instead of Donald Trump—”

“Dude,” says Ringlets. “Andrew Peyton isn’t running for president.”

“I know, but—”

Andrew Peyton, if he wins the VA delegate seat in next week’s election, will tilt our state bluer.

Ringlets has told me she’ll make Sunday supper. She’ll cobble something out of the terrible pile-up in the fridge.

Close at her elbow, I stare. Figs. She’s sauteing leftover figs from the restaurant where she works, ugly dry things. With them in the pan are a sampling of my choice unpitted black olives I keep half hidden at the back of the fridge.

She’s gotten out leftover rice, too—my failed Afghani rice from an earlier meal, and the restaurant’s wild-rice leavings. But that might not be enough, so she’s also started more, plain white. It’s in the rice cooker. To the mishmash she’ll add this and this and this middling scrap, anything of interest on hand. It’s how she likes to cook, she says. She just dumps stuff in.

A pottage of sorts, one nobody in the world has ever eaten before, because there’s no recipe and no precedent, is on the way. Still, her concocting is not without rhyme or reason. I can see some sense. We will not starve.

But in the downstairs bedroom, not one shred of sanity lingers.

A person can’t just walk around in there.

I’ve given Sister Braids, runny nosed and flushed, her own trash basket to carry room to room, for her balled-up Kleenexes, so they mostly hit the basket, not the floor. Otherwise everything lies out in the open in staggering disarray, plopped and draped like overdose victims. Maybe it’s actually a system. I can’t tell.

Her cold is taking its toll. She sleeps and sleeps and sleeps.

The AirPods go missing. Of course. And if they’re somewhere in the jumble of covers, or mixed up with the togs and duds and garbs and glad rags and getups, how will they ever get dug out?

A frazzled search. A halt to the search. More searching. They turn up in a drawer by the kitchen stove. I think I know who put them there. I don’t think me.

Sunday, getting ready for church, I steal some rightful moments in the bedroom. Pulling on my leggings, by accident I step on what looks to be a pouch for cosmetics. The cloth, up close, is patterned with peaches and apples and tangerine slices, and I wonder if I’ve broken anything. All manner of jars and tubes could be in there. The supply Braids brought with her, I had to clear off some shelf space in the bathroom.

I confess to Braids. It’s just pencils, she says.

Early morning, oh blessed hush, the world beyond the windows not yet stirred, just a lamp or two lit, our heads awake but our heaps of blanketssheetspillows still in shambles, Sister Braids emerges from her room aglow. All that rest.

She’s wondering about the noise in the walls.

What noise? we ask. We’ve not heard it yet, this season. But it must be time. Tight as we made our house, shivering mice manage to squeeze into the dead space above our bedroom ceiling. Just up there, that’s all, and soon the traps snap. Over at Braids’s place, though, it’s a different story. Big and old and leaky as the house is, any time of year the rodents can pretty much walk right in, switching their tails.

“During the night,” she tells us now, “if I get up and turn on the light, I might catch one cowering behind my beanbag.”

She just really likes it here.

Days later the carpets are still strung with cushion feathers and Kleenex shreds and undoubtedly, if I’d peer hard, some long crinkly blond hairs. They’ll go. And no factoids intruding. Touslyhead forgot to take home his bone he found and whittled to a point, maybe for a spear tip, but next time he’s here I’ll remind him. Picking through our platefuls of what’s left of Ringlets’s cooking—gourmet hodgepodge, we named it—I can count 14 different components (if the rice counts as three). This includes wilted almonds and cashews, chopped-up pod peas, ramen noodles, and a golden raisin. Inconceivable.

The silence is thrilling. But so is knowing we were trusted. For whole long days in the chilly autumn the threesome’s parents left them to us. The birds flew off and sang.

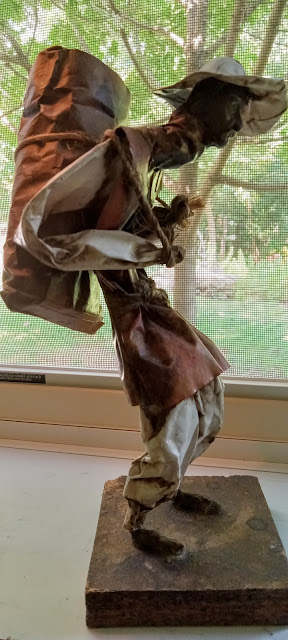

Clymer & Kurtz in Pittsburgh. Footage credit: Zachary Kurtz.

The joys of grandparenting💖

ReplyDelete